- Delegating closures to C# (26 Feb 2006)

- Blame CoCreate, for instance (14 Feb 2006)

- Beware of unknown enumerators (26.1.2006)

- Should Lisp programmers be slapped in public? (17.1.2006)

- To cut a long filename short, I lost my mind (8.1.2006)

- What's my email address? (4 Jan 2006)

- Fingerpointing at smart pointers (31 Dec 2005)

- Should type be of type Type? (31 Dec 2005)

Delegating closures to C# (26 Feb 2006)

Last time, I looked at how closures work in Lisp, and tried to mimick them in C++ (without success) using function objects. To recap, a closure can be thought of as:- A function pointer referring to the code to be executed

- A set of references to frames on the heap, namely references to all bindings of any free variables which occur in the code of the function.

class TestDelegate

{

public delegate void MyDelegate();

public MyDelegate GetDelegate()

{

string s = "Hiya";

return delegate() { Console.WriteLine(s); }; // anon delegate

}

static void Main(string[] args)

{

TestDelegate p = new TestDelegate();

MyDelegate anonDel = p.GetDelegate();

anonDel();

}

}

In the anonymous delegate, s is a free variable; the code compiles because

the delegate refers to the definition of s in the surrounding code.

If you run the above code, it will indeed print "Hiya", even though

we are calling the delegate from Main, i.e. after we have left

GetDelegate() which assigns that string to a local variable.

This is quite cool, considering that the .NET CLR uses a conventional

stack and probably wasn't designed to run Lisp or Scheme all day. How do they

do this?

Let's look at the disassembled code of GetDelegate() (using .NET Reflector,

of course):

public TestDelegate.MyDelegate GetDelegate()

{

TestDelegate.<>c__DisplayClass1 class1 = new TestDelegate.<>c__DisplayClass1();

class1.s = "Hiya";

return new TestDelegate.MyDelegate(class1.<GetDelegate>b__0);

}

So the compiler morphed our code while we were looking the other way!

Instead of assigning "Hiya" to a local variable, the code instantiates

a funky <>c__DisplayClass1 object, and that object apparently has a

member called s which holds the string. The <>c__DisplayClass1 class

also has an equivalent of the original GetDelegate function, as it seems.

Hmmm.... very puzzling - let's look at the definition of that proxy

class now:

[CompilerGenerated]

private sealed class <>c__DisplayClass1

{

// Methods

public <>c__DisplayClass1();

public void <GetDelegate>b__0();

// Fields

public string s;

}

public void <GetDelegate>b__0()

{

Console.WriteLine(this.s);

}

Aha, now we're getting somewhere. The compiler moved the code in the anonymous delegate

to the function <>c__DisplayClass1::<GetDelegate>b__0. This function

has access to the field s, and that field is initialized by the

compiler when the proxy object is instantiated.

So when the C# compiler encounters an anonymous delegate,

it creates a proxy object which holds all "bindings" (in Lisp terminology)

of free variables in the code of the delegate. That object is kept on the heap

and can therefore outlive the original GetDelegate(), and that is why we

can call the delegate from Main and still print the expected string

instead of referring to where no pointer has gone before.

I find this quite a cool stunt; I'm impressed by how the designers of C# are

adding useful abstractions to the language. Lisp isn't the only language which

supports closures, and maybe wasn't even the first, but I'm pretty sure that

the folks at Microsoft were probably influenced by either Lisp (or Scheme)

while developing anonymous delegates. It is amazing how such an old

language continues to inspire other languages to this day.

And that is, after reading a couple of good books and enlightening articles,

what I understood about closures. Now, as a long-time boneheaded C++ programmer, I might

have gotten it all wrong, and this blog entry is actually one way to test

my assumptions; if my views are blatantly misleading, then hopefully somebody will

point this out. (Well, if anybody reads this at all, of course.)

What a simple and amazing concept those closures really are! I only had to

shed all my preconceptions about the supposedly one and only way to call and execute

functions and how to keep their parameters and variables on a stack...

Closures are definitely very handy in all situations where callbacks are registered.

Also, I already alluded to the fact that you could possibly build an object concept on top of

closures in Lisp. And doesn't "snapshot of a function in execution" sound

frighteningly close to "continuation"

or "coroutines"? (Answer: Yes, kind of, but not quite. But that's a different story.)

I'm still trying to learn what closures do and how to best apply them in practice.

But that doesn't mean they are constructs for the ivory tower: Knowing about them

helped me only recently to diagnose and explain

what originally looked like a memory leak in some Lisp test code that we had written.

The final word of the jury is still out, but this is probably not a real leak,

rather a closure which holds on to the binding of a variable, so that the garbage

collector cannot simply free the resources associated with that variable.

Blame CoCreate, for instance (14 Feb 2006)

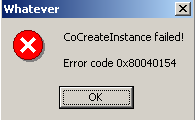

The company I work for is called CoCreate. The name was chosen because the company's mission is all about collaboratively creating things. That's all nice and dandy, but I guess the team who picked the name didn't include a programmer, and so they overlooked something pretty obvious which causes mild confusion every now and then. Most programmers, when confronted with our company name, think of COM. After all, one of the most important functions in all of the COM libraries prominently displays our company name: CoCreateInstance. Now, if a programmer thinks about COM (and hence software) when she hears about us, that's probably fine, because, after all, we're in the business to make and sell software. However, customers are not necessarily that technology-savvy, nor should they have to be. A while ago, a customer complained that our software was sloppy because it wouldn't uninstall itself properly and leave behind traces in the system. Our installer/uninstaller tests didn't seem to confirm that. So we asked the customer why he thought we were messing with his system. "Well", he said, "even after I uninstall your stuff, I still get those CoCreate error messages." The customer sent a screenshot - it showed a message box,

displayed by an application which shall remain unnamed, saying

that "CoCreateInstance failed" and mumbling some COM error

codes!

It took us a while to explain to the customer that no, we

did not install this CoCreateInstance thing on the system,

and that it is a system function, and if we actually tried to

uninstall it along with our application as he requested (kind of),

he wouldn't be terribly happy with his system any longer, and

that the other app was actually trying to report to the customer that

it had found a problem with its COM registration, and that this should

be looked after, not our uninstaller. Phew.

Now if only we had the time-warping powers of the publishers

of "The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy", we'd send our

company marketing materials back into time before Microsoft invented

COM, and then sue the living daylights out of them. Well, if we were

evil, that is

The customer sent a screenshot - it showed a message box,

displayed by an application which shall remain unnamed, saying

that "CoCreateInstance failed" and mumbling some COM error

codes!

It took us a while to explain to the customer that no, we

did not install this CoCreateInstance thing on the system,

and that it is a system function, and if we actually tried to

uninstall it along with our application as he requested (kind of),

he wouldn't be terribly happy with his system any longer, and

that the other app was actually trying to report to the customer that

it had found a problem with its COM registration, and that this should

be looked after, not our uninstaller. Phew.

Now if only we had the time-warping powers of the publishers

of "The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy", we'd send our

company marketing materials back into time before Microsoft invented

COM, and then sue the living daylights out of them. Well, if we were

evil, that is  My memory took a little longer to swap back in, but while writing

the above, it dawned on me that this incident wasn't the only one of

its kind: Somebody had upgraded to a new PC and installed all applications

except CoCreate's. Then, while syncing to his Palm Pilot, he got

an "OLE CoCreateInstance Failed" error message, and started to

search high and low on his shiny new PC for traces of CoCreate

applications or components.

Puzzled, he posted to a newsgroup, and I replied with tongue-in-cheek:

My memory took a little longer to swap back in, but while writing

the above, it dawned on me that this incident wasn't the only one of

its kind: Somebody had upgraded to a new PC and installed all applications

except CoCreate's. Then, while syncing to his Palm Pilot, he got

an "OLE CoCreateInstance Failed" error message, and started to

search high and low on his shiny new PC for traces of CoCreate

applications or components.

Puzzled, he posted to a newsgroup, and I replied with tongue-in-cheek:

Let me explain: When we kicked off CoCreate as a company, we sat together and thought about awareness strategies for the new company. So we called our buddies from Microsoft and asked them to name some API functions after us, and in exchange we would port our software to Windows NT. Neat scheme, and as you discovered on your system, the cooperation between the two companies worked just fine. [... skipping explanation of the technical issue and hints on how to fix registry issue on the system ...] The next step for CoCreate towards world domination will be to talk to some of our buddies in, say, Portugal, and offer them to develop a Portugese version of our application if they name their country after us.Would I get away with a response like this if I was a support engineer? Maybe not. One more thing to like about being a software developer

(Everybody in the newsgroup had a good chuckle back then.)

(Everybody in the newsgroup had a good chuckle back then.)

Beware of unknown enumerators (26.1.2006)

The other day, I was testing COM clients which accessed a collection class via a COM-style enumerator (IEnumVARIANT). And those clients crashed

as soon as they tried to do anything with the enumerator. Of course, the

same code had worked just fine all the time before. What changed?

In COM, a collection interface often implements a function called GetEnumerator()

which returns the actual enumerator interface (IEnumVARIANT), or rather,

a pointer to the interface. In my case, the signature of that function was:

HRESULT GetEnumerator(IUnknown **);Didn't I say that

GetEnumerator is supposed to return an IEnumVARIANT

pointer? Yup, but for reasons which I may cover here in one

of my next bonus lives, that signature was changed from IEnumVARIANT to IUnknown.

This, however, is merely a syntactic change - the function actually still

returned IEnumVARIANT pointers, so this alone didn't explain the crashes.

Well, I had been bitten before by smart pointers,

and it happened again this time! The COM client code declared a smart

pointer for the enumerator like this:

CComPtr<IEnumVARIANT> enumerator = array->GetEnumerator();This is perfectly correct code as far as I can tell, but it causes a fatal avalanche:

- The compiler notices that

GetEnumeratorreturns anIUnknownpointer. This doesn't match the constructor of this particular smart pointer which expects an argument of typeIEnumVARIANT *. - So the compiler looks for other matching constructors.

- It doesn't find a matching constructor in

CComPtritself, butCComPtris derived fromCComPtrBasewhich has an undocumented constructorCComPtrBase(int). - To match this constructor, the compiler converts the

return value of

GetEnumerator()into aboolvalue which compresses the 32 or 64 bits of the pointer into a single bit! (Ha! WinZip, can you beat that?) - The boolean value is then passed to the

CComPtrBase(int)constructor. - To add insult to injury, this constructor doesn't even use its argument and instead resets the internally held interface pointer to 0.

GetEnumerator declaration was bogus.

But neither C++ nor ATL really helped to spot this issue.

On the contrary, the C++ type system (and its implicit

type conversions) and the design of the ATL smart pointer classes

collaborated to hide the issue away from me until it was too late.

Should Lisp programmers be slapped in public? (17.1.2006)

After fixing a nasty bug today, I let off some steam by surfing the 'net for fun stuff and new developments. For instance, Bjarne Stroustrup recently reported on the plans for C++0x. I like most of the stuff he presents, but still was left disturbingly unimpressed with it. Maybe it's just a sign of age, but somehow I am not really thrilled anymore by a programming language standard scheduled for 2008 which, for the first time in the history of the language, includes something as basic as a hashtable. Yes, I know that pretty much all the major STL implementations already have hashtable equivalents, so it's not a real issue in practice. And yes, there are other very interesting concepts in the standard which make a lot of sense. Still - I used to be a C++ bigot, but I feel the zeal is wearing off; is that love affair over? Confused and bewildered, I surf some other direction, but only to have Sriram Krishnan explain to me that Lisp is sin. Oh great. I happen to like Lisp a lot - do I really deserve another slap in the face on the same day? But Sriram doesn't really flame us Lisp geeks; quite to the contrary. He is a programmer at Microsoft and obviously strongly impressed by Lisp as a language. His blog entry illustrates how Lisp influenced recent developments in C# - and looks at reasons why Lisp isn't as successful as many people think it should be. Meanwhile, back in the C++ jungle: Those concepts are actually quite clever, and solve an important problem in using C++ templates. In a way, C++ templates use what elsewhere is called duck typing. Why do I say this? Because the types passed to a template are checked implicitly by the template implementation rather than its declaration. If the template implementation says f = 0 andf is a template

parameter, then the template assumes that f provides an assignment

operator - otherwise the code simply won't compile. (The difference

to duck typing in its original sense is that we're talking about

compile-time checks here, not dynamic function call resolution at run-time.)

Hence, templates do not require types to derive from certain classes or

interfaces, which is particularly important when using templates for primitive

types (such as int or float). However, when the type check fails,

you'll drown in error messages which are cryptic enough to violate

the Geneva convention. To fix the error, the user of a template often

has to inspect the implementation of the template to understand

what's going on. Not exactly what they call encapsulation.

Generics in .NET improve on this by specifying constraints explicitly:

static void Foobar<T>(IFun<T> fun) where T : IFunny<T>

{

... function definition ...

}

T is required to implement IFunny. If it doesn't, the compiler will

tell you that T ain't funny at all, and that's that. No need to dig

into the implementation details of the generic function.

C++ concepts extend this idea: You can specify pretty arbitrary restrictions

on the type. An example from Stroustrup's and Dos Reis' paper:

concept Assignable<typename T, typename U=T> {

Var<T> a;

Var<const U> b;

a = b;

};

;; using this in a template definition:

template <typename T, typename U>

where Assignable<T, U>

... template definition ...

So if T and U fit into the Assignable concept, the compiler will

accept them as parameters of the template. This is cute: In true C++

tradition, this provides maximum flexibility and performance,

but solves the original problem.

Still, that C# code is much easier on the eye...

To cut a long filename short, I lost my mind (8.1.2006)

Yesterday, I explained how easy it is to inadvertedly load the same executable twice into the same process address space - you simply run it using its short DOS-ish filename (likeSample~1.exe)

instead of its original long filename (such as SampleApplication.exe).

For details, please consult the original blog entry.

I mentioned that one fine day I might report how exactly this happened

to us, i.e. why in the world our app was started using its short filename.

Seems like today is such a fine day  Said application registered itself as a COM server, and it does so using

the services of the ATL Registrar.

Upon calling

Said application registered itself as a COM server, and it does so using

the services of the ATL Registrar.

Upon calling RegisterServer, the registrar will kindly create all the required

registry entries for a COM server, including the LocalServer entry which

contains the path and filename of the server. Internally, this will call the

following code in atlbase.h:

inline HRESULT WINAPI CComModule::UpdateRegistryFromResourceS(UINT nResID,

BOOL bRegister, struct _ATL_REGMAP_ENTRY* pMapEntries)

{

USES_CONVERSION;

ATL::CRegObject ro;

TCHAR szModule[_MAX_PATH];

GetModuleFileName(_pModule->GetModuleInstance(), szModule, _MAX_PATH);

// Convert to short path to work around bug in NT4's CreateProcess

TCHAR szModuleShort[_MAX_PATH];

GetShortPathName(szModule, szModuleShort, _MAX_PATH);

LPOLESTR pszModule = T2OLE(szModuleShort);

...

Aha! So ATL deliberately converts the module name (something like SampleApplication.exe)

into its short-name equivalent (Sample~1.exe) to work around an issue in the

CreateProcess implementation of Windows NT.

MSKB:179690

describes this problem: CreateProcess could not always handle blanks in pathnames

correctly, and so the ATL designers had to convert the path into its short-path

version which converts everything into an 8+3 filename and hence guarantees that

the filename contains no blanks.

Adding insult to injury, MSKB:201318

shows that this NT-specific bug fix in ATL has a bug itself... and, of course, our problem is,

in fact, caused by yet another bug in the bug fix (see earlier blog entry).

For my application, the first workaround was to use a modified version of atlbase.h which checks the

OS version; if it is Windows 2000 or later, no short-path conversion

takes place. Under Windows NT, however, we're caught in a pickle: Either we

use the original ATL version of the registration code and thus map the executable

twice into the address space, or we apply the same fix as for Windows 2000,

and will suffer from the bug in CreateProcess if the application is installed

in a path which has blanks in the pathname.

In my case, this was not a showstopper issue because the application is targeting Windows 2000 and XP

only, so I simply left it at that.

Another approach is to use the AddReplacement

and ClearReplacements APIs of the ATL registrar to set our own conversion rules

for the module name and thereby override ATL's own rules for the module name:

#include <atlbase.h>

#include <statreg.h>

void RegisterServer(wchar_t *widePath, bool reg)

{

ATL::CRegObject ro;

ro.AddReplacement(L"Module", widePath);

reg ? ro.ResourceRegister(widePath, IDR_REGISTRY, L"REGISTRY") :

ro.ResourceUnregister(widePath, IDR_REGISTRY, L"REGISTRY");

}

What's my email address? (4 Jan 2006)

On various occasions, I had already tried to make sense out of directory services such as LDAP and Microsoft's ADSI. Now, while that stuff is probably not rocket science, the awkward terminology and syntax in this area have always managed to shy me away; most of the time, there was another way to accomplish the same without going through LDAP or ADSI, and so I went with that. This time, the task was to retrieve the email address (in SMTP format) for a given user. In my first attempt, I tried to tap the Outlook object model, but then figured that a) there are a few systems in the local domain which do not have Outlook installed and b) accessing Outlook's address info causes Outlook to display warnings to the user reporting that somebody apparently is spelunking around in data which they shouldn't be accessing. Which is probably a good idea, given the overwhelming "success" of Outlook worms in the past, but not exactly helpful in my case. However, everybody here is connected to a Windows domain server and therefore has access to its AD services, so that sounded like a more reliable approach. I googled high and low, dissected funky scripts I found out there and put bits of pieces of them together again to form this VBscript code:

user="Claus Brod"

context=GetObject("LDAP://rootDSE").Get("defaultNamingContext")

ou="OU=Users,"

Set objUser = GetObject("LDAP://CN=" & user & "," & ou & context)

WScript.Echo(objUser.mail)

groups=objUser.Get("memberOf")

For Each group in groups

WScript.Echo(" member of " & group)

Next

This works, but the OU part of the LDAP string (the "ADsPath") depends on the local

organizational structure and needs to be adapted for each particular environment;

I haven't found a good way to generalize this away. Hints most welcome.

PS: For those of you on a similar mission, Richard Mueller provides some helpful

scripts at http://www.rlmueller.net/freecode3.htm.

Fingerpointing at smart pointers (31 Dec 2005)

In an ATL COM client which uses#import to generate wrapper code for objects,

I recently tracked down a subtle reference-counting issue down to this single line:

IComponentArray *compArray = app->ILoadComponents();This code calls a method

ILoadComponents on an application object which returns

an array of components. Innocent-looking as it is, this one-liner caused me

quite a bit of grief. If you can already explain what the reference counting

issue is, you shouldn't be wasting your time reading this blog. For the rest

of us, I'll try to dissect the problem.

(And for those who don't want to rely on my explanation: After I had learnt

enough about the problem so that I could intelligently feed Google with

search terms, I discovered a Microsoft

Knowledge Base

article on this very topic. However, even after reading the article, some details

were still unclear to me, especially since I don't live and breathe ATL all day.)

The #import statement automatically generates COM wrapper functions. For

ILoadComponents, the wrapper looks like this:

inline IComponentArrayPtr IApplication::ILoadComponents () {

struct IComponentArray * _result = 0;

HRESULT _hr = raw_ILoadComponents(&_result);

if (FAILED(_hr)) _com_issue_errorex(_hr, this, __uuidof(this));

return IComponentArrayPtr(_result, false);

}

IComponentArrayPtr is a typedef-ed template instance of

_com_ptr_t.

The constructor used in the code snippet above will only call AddRef

on the interface pointer if its second argument is true. In our case, however,

the second arg is false, so AddRef will not be called. The IComponentArrayPtr

destructor, however, always calls Release().

Feeling uneasy already? Yeah, me too. But let's follow the course of action a little

bit longer. When returning from the wrapper function, the copy constructor of the

class will be called, and intermediate IComponentArrayPtr objects will be

created. As those intermediate objects are destroyed, Release() is called.

Now let us assume that the caller looks like above, i.e. we assign the return value

of the wrapper function to a CComPtr<IComponentArray> type. The sequence

of events is as follows:

- Wrapper function for

ILoadComponentsis called. - Wrapper function calls into the COM server. The server returns

an interface pointer for which

AddRef()was called (at least) once inside the server. The reference count is 1. - Wrapper function constructs an

IComponentArrayPtrsmart pointer object which simply copies the interface pointer value, but does not callAddRef(). The refcount is still 1.

CComPtr<IComponentArray> components = app->ILoadComponents();

ILoadComponents returns an object of type IComponentArrayPtr. At this

point, the reference count for the interface is 1 (see above). The

The compiler casts IComponentArrayPtr to IComponentArray*, then calls the

CComPtr assignment operator which copies the pointer and calls AddRef on it.

The refcount is now 2. At the completion of the statement, the temporary

IComponentArrayPtr is destroyed and calls Release on the interface. The

refcount is 1. Just perfect.

Now back to the original client code:

IComponentArray *compArray = app->ILoadComponents();Here, we assign to a "raw" interface pointer, rather than to a

CComPtr,

When returning from the wrapper function,

the refcount for the interface is 1. The compiler casts IComponentArrayPtr

to IComponentArray* and directly assigns the pointer. At the

end of the statement (i.e. the end of the "full expression"), the temporary

IComponentArrayPtr is destroyed and calls Release, decrementing the

refcount is 0. The object behind the interface pointer disappears, and

subsequent method calls on compArray will fail miserably or crash!

So while ATL, in conjunction with the compiler's #import support,

is doing its best to shield us from the perils of reference counting

bugs, it won't help us if someone pulls the plug from the ATL force-field

generator by incorrectly mixing smart and raw pointers.

This kind of reference counting bug would not have occurred if I had

used raw interface pointers throughout; the mismatch in calls to AddRef

and Release would be readily apparent in such code. However, those

smart pointers are indeed really convenient in practice because

they make C++ COM code so much simpler to read. However, they do not

alleviate the programmer from learning about the intricacies of

reference counting. You better learn your IUnknown before you do

CComPtr.

This reminds me of Joel Spolsky's

The Perils of JavaSchools,

which is soooo 1990 (just like myself), but good fun to read.

Should type be of type Type? (31 Dec 2005)

The other day, we were writing some .NET code for which we produced COM wrappers, including a type library (throughtlbexp). One of the exported methods

looked like this (in Managed C++):

void AddButton(String *title, String *icon, ActionType type);In a COM test client which referred to said type library, the compiler reported inexplicable errors. They hinted that the parameter named (!)

type somehow was thought to be of type System.Type...

but why? type is correctly declared as an ActionType, not as System::Type!

I won't tell you what other means we used to track down this issue;

let me just advise you to clean those chicken blood stains as early as

possible, before they stick to your keyboard just like, well, chicken blood .-)

In the end, Adam Nathan's blue bible had the right hint for us: Type libraries maintain a case-insensitive

identifier table. Once an identifier has been added to the table in one

case, any subsequent attempts to add the identifier to the table again

will simply fail, regardless of the case.

So in our example, the first "type"-ish identifier which was added to the table

was System::Type. (Or maybe it was actually a parameter called type which

was of type System::Type?). Later, the parameter name type was encountered,

but no longer added to the table because of its unlikely relative which made it

into the table first. Any subsequent references to anything called "type"

or "Type" or "tYPE" would then resolve to System::Type, with the aforementioned

consequences.

Revision: r1.2 - 30 Mar 2006 - 20:01 - ClausBrod