- Aggressive predictions (03 May 2008)

- This blog considered illegal (13 Apr 2008)

- So long, and thanks for all the functional fish! (30 Mar 2008)

- CLR? To me, that's "Common Lisp Runtime"! (12 Mar 2008)

- In the presence of genius (06 Mar 2008)

- Sniffing for crashes (09 Jan 2008)

- Entendämmerung (02 Jan 2008)

Aggressive predictions (03 May 2008)

This blog considered illegal (13 Apr 2008)

private, and

the author of that code wasn't supposed to change the class under test, or did not have

access to it.

This disgusting hack was probably meant as a stopgap solution, but then remained in the code

for way too much time - until it was re-discovered and became a part of our local programming folklore.

I was actually grateful for this hack - without it, I'd probably still be searching for a

name for my blog!

And then, just a few days ago, I came across the following excerpt from the standard for

the C++ standard library (ISO/IEC 14882:1998(E),

section 17.4.3.1.1):

A translation unit that includes a header shall not contain any macros that define names declared or defined in that header. Nor shall such a translation unit define macros for names lexically identical to keywords.Good heavens, my blog is cursed upon by the standard! Expelled will I be from the C++ community! Never will I be on a first-name basis with Mr. Stroustrup! What have I done...

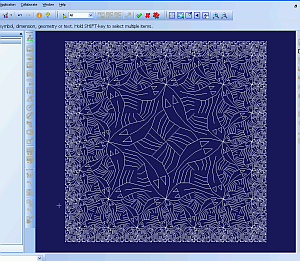

So long, and thanks for all the functional fish! (30 Mar 2008)

;; -*-Lisp-*-

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;; Description: Wrapper to run Frank Buss' functional geometry code

;; in CoCreate Modeling

;; Author: Claus Brod

;; Language: Lisp

;;

;; (C) Copyright 2008 Claus Brod, all rights reserved

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;

(in-package :clausbrod.de)

(use-package :oli)

(export '(plot-escher))

;; Allow using lambda without quoting it via #' first

;; (No longer required in CoCreate Modeling 2008 and later.)

(defmacro lambda (&rest body)

`(function (lambda ,@body)))

(defparameter *our-loadpath* *load-truename*)

(load (format nil "~A/functional.lsp"

(directory-namestring *our-loadpath*)))

;; Modeling-specific plotter function

(defun plot-annotation (p)

(let ((tempfile (format nil "~A/test.mac" (oli:sd-inq-temp-dir)))

(scale 500.0))

(startup::activate-annotation)

(with-open-file (s tempfile

:direction :output :if-exists :supersede)

(format s "line~%")

(dolist (line (funcall p '(0 0) '(1 0) '(0 1)))

(destructuring-bind ((x0 y0) (x1 y1)) line

(format s " ~D,~D ~D,~D~%"

(* scale (float x0))

(* scale (float y0))

(* scale (float x1))

(* scale (float y1)))))

(format s "end"))

(oli:sd-execute-annotator-command

:cmd (format nil "input '~A'" tempfile))

(docu::docu_vp :fit_vp)

(delete-file tempfile)))

;; Shortcut for the Escher fish drawing

(defun plot-escher()

(plot-annotation *fishes*))

The loader code adds the definition for the lambda macro

which is missing so far in CoCreate Modeling, loads Frank's code, and then adds a

plotter function which creates output in a 2D Annotation window.

Usage instructions:

- Download Frank's code from his site

and save it as

functional.lsp. - Download the loader code and save it into the same directory.

- Load the loader Lisp code into CoCreate Modeling 2007 or higher.

- In the user input line, enter

(clausbrod.de:plot-escher)

CLR? To me, that's "Common Lisp Runtime"! (12 Mar 2008)

In other words, I want Common Lisp to become a mainstream language - which it arguably

isn't, even though pretty much everybody agrees about its power and potential.

One way to acquire mainstream super-powers is to team up with one of the

planet's most potent forces in both software development and marketing: Microsoft. This

is the strategic reason for my proposal. Yes, I know, many Lisp gurus and geeks out

couldn't care less about Microsoft and the Windows platform, or even shudder at the

thought. But there are also tactical and technical reasons, so bear with me for a minute

before you turn on your flamethrowers.

When I say Microsoft, I really mean .NET and its Common Language Runtime. Well, that's

what they say is how to spell out CLR. But I claim that the L could just

as well stand for Lisp, as the CLR, particularly in conjunction with the

Dynamic Language Runtime

extensions which Microsoft is working on, is a suspiciously suitable platform to build an

implementation of Common Lisp upon: Not only does it provide a renowned garbage collector

(designed by former Lisp guru

Patrick

Dussud)

and a rich type system, it also has extensive reflection and code generation support,

and - through the DLR - fast dynamic function calls,

AST processing and compilation,

debugger integration, REPL support, and all that jazz. It's no coincidence

that languages such as C# and even VB.NET are picking up new dynamic language

features with every new release, and that Microsoft has even added a new functional

language, F#, to the set of languages which are (or will be)

fully integrated into Visual Studio.

The wave is coming in, and we better not miss it!

Best of all, it's not just about Windows anymore: The DLR and IronPython also

run on top of

Mono. Mono is available for Linux, Solaris, Mac OS X,

various BSD flavors as well as for Windows, so layering Common Lisp on

top of the CLR doesn't limit us to the Windows platform at all!

Note that I explicitly said "Common Lisp". I think that it's vital

for an implementation on top of the CLR/DLR to be truly standards-compliant. I am not alone

in this belief: In the

IronPython and IronRuby

projects, Microsoft went to great lengths to make sure that the implementations are true

to the original language.

What would this buy us? Well, one recurring and dominant theme in discussions about

the viability of Lisp as a mainstream language is the perceived or real

lack of actively maintained libraries and tools. With the approach I'm outlining,

we could still run all those excellent existing

Common Lisp libraries

and projects

out

there,

but we'd also be able to use the huge body of code both in the .NET framework

itself and in third-party .NET components. Common Lisp code could seamlessly

call into a library written in, say, C#, and VB.NET programmers would be able

to consume Common Lisp libraries!

Taking it a little further, we could also integrate with Visual Studio. Where I work,

it would make all the difference in the world if we could edit, run and debug

our Lisp code from within Visual Studio. I'm convinced that this would

attract a large new group of programmers to Common Lisp. Hordes of them, in fact

In other words, I want Common Lisp to become a mainstream language - which it arguably

isn't, even though pretty much everybody agrees about its power and potential.

One way to acquire mainstream super-powers is to team up with one of the

planet's most potent forces in both software development and marketing: Microsoft. This

is the strategic reason for my proposal. Yes, I know, many Lisp gurus and geeks out

couldn't care less about Microsoft and the Windows platform, or even shudder at the

thought. But there are also tactical and technical reasons, so bear with me for a minute

before you turn on your flamethrowers.

When I say Microsoft, I really mean .NET and its Common Language Runtime. Well, that's

what they say is how to spell out CLR. But I claim that the L could just

as well stand for Lisp, as the CLR, particularly in conjunction with the

Dynamic Language Runtime

extensions which Microsoft is working on, is a suspiciously suitable platform to build an

implementation of Common Lisp upon: Not only does it provide a renowned garbage collector

(designed by former Lisp guru

Patrick

Dussud)

and a rich type system, it also has extensive reflection and code generation support,

and - through the DLR - fast dynamic function calls,

AST processing and compilation,

debugger integration, REPL support, and all that jazz. It's no coincidence

that languages such as C# and even VB.NET are picking up new dynamic language

features with every new release, and that Microsoft has even added a new functional

language, F#, to the set of languages which are (or will be)

fully integrated into Visual Studio.

The wave is coming in, and we better not miss it!

Best of all, it's not just about Windows anymore: The DLR and IronPython also

run on top of

Mono. Mono is available for Linux, Solaris, Mac OS X,

various BSD flavors as well as for Windows, so layering Common Lisp on

top of the CLR doesn't limit us to the Windows platform at all!

Note that I explicitly said "Common Lisp". I think that it's vital

for an implementation on top of the CLR/DLR to be truly standards-compliant. I am not alone

in this belief: In the

IronPython and IronRuby

projects, Microsoft went to great lengths to make sure that the implementations are true

to the original language.

What would this buy us? Well, one recurring and dominant theme in discussions about

the viability of Lisp as a mainstream language is the perceived or real

lack of actively maintained libraries and tools. With the approach I'm outlining,

we could still run all those excellent existing

Common Lisp libraries

and projects

out

there,

but we'd also be able to use the huge body of code both in the .NET framework

itself and in third-party .NET components. Common Lisp code could seamlessly

call into a library written in, say, C#, and VB.NET programmers would be able

to consume Common Lisp libraries!

Taking it a little further, we could also integrate with Visual Studio. Where I work,

it would make all the difference in the world if we could edit, run and debug

our Lisp code from within Visual Studio. I'm convinced that this would

attract a large new group of programmers to Common Lisp. Hordes of them, in fact  Yes, I know about SLIME and

Dandelion and

Cusp, and I'm perfectly aware that

Emacs will simultaneously

iron your shirts, whistle an enchanting tune, convincingly act on your behalf

in today's team phone conference, and book flights to the Caribbean

while compiling, debugging, refactoring and possibly even writing all your

Lisp code for you in the background. Still, there's a whole

caste of programmers who never felt any desire to reach beyond the confines

of the Visual Studio universe, and are perfectly happy with their IDE,

thank you very much. What if we could sell even those programmers on

Common Lisp? (And yes, of course you and I could continue to use our

beloved Emacs.)

Now, all these ideas certainly aren't original. There are a number of projects

out there born out of similar motivation:

Yes, I know about SLIME and

Dandelion and

Cusp, and I'm perfectly aware that

Emacs will simultaneously

iron your shirts, whistle an enchanting tune, convincingly act on your behalf

in today's team phone conference, and book flights to the Caribbean

while compiling, debugging, refactoring and possibly even writing all your

Lisp code for you in the background. Still, there's a whole

caste of programmers who never felt any desire to reach beyond the confines

of the Visual Studio universe, and are perfectly happy with their IDE,

thank you very much. What if we could sell even those programmers on

Common Lisp? (And yes, of course you and I could continue to use our

beloved Emacs.)

Now, all these ideas certainly aren't original. There are a number of projects

out there born out of similar motivation:

- L Sharp .NET - a Lisp-based scripting language for .NET by Rob Blackwell

- Yarr - Lisp-based scripting language for .NET based on L Sharp

- dotLisp - a Lisp dialect for .NET, written by Rich Hickey (of Clojure fame)

- Rich Hickey mentioned in a presentation that the original versions of Clojure were actually written to produce code for the CLR

- IronLisp - Lisp on top of the DLR, initiated by Llewellyn Pritchard, who later decided to tackle IronScheme instead

- There's a even a toy Common Lisp implementation by Microsoft which they shipped as a sample in the .NET Framework SDK (and now as part of the Rotor sources)

- Joe Marshall has an interesting project which looks like Lisp implemented in C#.

- LispSharp is a CLR-based Lisp compiler (Mirko Benuzzi)

- ClearLisp is another CL dialect written in C# by Jan Tolenaar.

- A LISP/Scheme language for .NET (Adam Milazzo)

- CLearSharp, by Ola Bini

- Joe Duffy's Sencha project

- VistaSmalltalk may not sound like Lisp, but it actually contains a Lisp engine (implemented in C#), and according to the architecture notes I found, Smalltalk is implemented on top of Lisp.

- CLinNET, by Dan Muller

- CarbonLisp, by Eric Rochester

- MBase, a "metaprogramming framework" providing a Lisp-like definition language

- Sohail Somani experiments with .NET IL generation from Lispy syntax

- RDNZL - .NET interop layer for Common Lisp (Edi Weitz)

- FOIL - Foreign object interface for Lisp (i.e. an interop layer) on top of both the JVM and the CLR, by Rich Hickey (again!) and Eric Thorsen

In the presence of genius (06 Mar 2008)

I sure hope I'll have a chance to meet Kent one day!

I sure hope I'll have a chance to meet Kent one day!

Sniffing for crashes (09 Jan 2008)

Well, I remember the basic approach, and I even took some notes back then which I will regurgitate

here and now. However, don't expect step-by-step instructions.

My goal was to take control of the crash reporting process in my application.

When an application crashes, Microsoft's official recommendation is that it should not

try to catch the fatal exception, but instead simply bail out, let Windows perform

its crash reporting rites, and then terminate. For various reasons, we needed more

control over the process, and so I set out on a discovery tour through

the Windows Error Reporting APIs which Microsoft introduced in Windows Vista. The

details of this epic saga can be found at:

Well, I remember the basic approach, and I even took some notes back then which I will regurgitate

here and now. However, don't expect step-by-step instructions.

My goal was to take control of the crash reporting process in my application.

When an application crashes, Microsoft's official recommendation is that it should not

try to catch the fatal exception, but instead simply bail out, let Windows perform

its crash reporting rites, and then terminate. For various reasons, we needed more

control over the process, and so I set out on a discovery tour through

the Windows Error Reporting APIs which Microsoft introduced in Windows Vista. The

details of this epic saga can be found at:

- The end is nigh (for my process)

- Crashing with style on Vista

- Crashing with style on Vista, part II

- Think globally, dump locally

- Don't dump Vista just yet; let Vista do the dumping!

- Elementary, my dear Watson!

crashme.exe could successfully dump its debris to Microsoft's

servers. Hence, the idea was to look at the network traffic and find the differences between

my crash reports and those produced by the proverbial crashme.exe.

I could have run the usual network sniffing suspects to decode LAN traffic including all the email exchanged

between my boss and his boss, of course. But there is an even easier and less controversial approach:

For corporate environments, where admins often need more control over the crash reporting

process, Microsoft introduced corporate error reporting (CER), where crashing systems can contact

a local server rather than sending all those confidential access violations to Microsoft.

There are registry entries

to set the server name and port for corporate error reporting:

-

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Windows Error Reporting\CorporateWERServer: Name of the local crash reporting server -

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Windows Error Reporting\CorporateWERPortNumber: Port number to be used for communication

CorporateWERServer so that it referred to my laptop. I did not set

the port number explicitly; using procmon,

I found that the default port is 1273.

On my laptop, I installed netcat and had it listen to

input from port 1273 (nc -l273 or something like that). Once the port was open, Vista started to

send HTTP POST requests to it - so the CER server really is a specialized HTTP server listening

to port 1273! Here's a typical request (slightly polished and anonymized) following a crash

in a sample app I was writing back then:

POST /stage2.htm HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: MSDW

Host: mylaptop:1273

Content-Length: 1110

Connection: Keep-Alive

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-16"?>

<WERREPORT xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance">

<MACHINEINFO machinename="myvistabox" os="6.0.6000.2.0.0.256.16" lcid="1033"/>

<USERINFO username="myvistabox\clausb"/>

<APPLICATIONINFO appname="werapitest.exe" apppath="C:\tmp\werapitest.exe"/>

<EVENTINFO reporttype="1" eventtime="128267449141252896" eventtype="werapitest (eventType)"

friendlyeventname="werapitest (friendly event name)" eventdescription="Critical runtime problem"/>

<SIGNATURE>

</SIGNATURE>

</WERREPORT>

By comparing this kind of payload with the traffic generated by a plain vanilla crashme.exe program,

I could experiment with the various WER APIs and settings until I had finally figured out how to

use them. Without crash report sniffing, I'd probably still be experimenting...

Entendämmerung (02 Jan 2008)

Revision: r1.1 - 06 Mar 2009 - 17:10 - ClausBrod